A long time ago, when I was still a student, I got my hands on a very fascinating book called "

The effects of nuclear weapons" from the

Atomic Energy Commission. It was filled with diagrams and tables and enabled you to calculate the effects of a nuclear attack. After five long hours, I got my first results. And it was 4 AM. I knew when I stayed on working and calculating, I was gonna lose a lot of sleep.

However, it was 1981 and at my college we had a highly modern machine: a real

PDP-11 with a massive memory of 256 kB and two (floppy) disk drives. Those were the days of the

NATO Double-Track Decision, which

large parts of the Dutch population opposed. I decided this program was going to be my contribution to that discussion. I called it TEONW (The Effects Of Nuclear Weapons). It is full of cynic puns against the

Reagan administration.

I spend nights digitizing the graphs in that book, and coding them in BASIC V10B-02. I had never heard of structured programming and to debug the program I needed a room as long as the listing. If the program said

GOTO 5670 I really crawled to line 5670! I never got all the bugs ironed out.

After I had finished college I no longer had access to a computer, but I printed a listing which I entered line by line in the

Sinclair ZX Spectrum. I also added some assembly to mimic the green-on-black terminal of the PDP-11.

When the Z80 Spectrum emulator of

Gerton Lunter came out, I took the

Betadisk, wrote BDDE (

BetaDisk Dump Extractor) and transferred the program to a .Z80 file,

which may still be found on the Internet. Ten years had gone by.

The .Z80 file was moved from MS-DOS to Linux. I extracted the code with

FUSE-utils "listbasic" and made it run under "

blassic". By then twenty years had passed.

In the meanwhile, I had been busy writing my

4tH compiler, which is a highly portable

bytecode Forth compiler. A few years ago, I added floating point support. What had begun its life as a little toy was now powerful enough to run a program like TEONW. Thirty years later.

TEONW is a relatively small program, just 13 kB source, but it is such an

awful mess that I was barely able to understand and code the entry of the basic parameters: yield, altitude and population density. If I ever wanted to convert this program I needed some help.

Badly..TEONW consists of about 500 lines, each with its own line number. Since it is written in

Minimal BASIC, every

IF-statement is followed by a

GOTO. No

ELSE, sorry. In order to expose the structure, I needed to get rid of all superfluous labels, i.e. the labels which were not jumped to by either a

GOSUB or

GOTO. For that I wrote a simple 4tH program, the "uBasic unlabeler" or

ubulabel.4th for short. It parses the BASIC program, makes a list of all

GOTO and

GOSUB labels and then removes all unused labels. That reduced the number of labels to about 100.

But I had still very little insight in the structure of the overall program. Comment was scarce and terse. Instead of making a flow diagram myself, I decided to let the computer do that for me. If you talk about generating diagrams, you talk about

Graphviz. This indispensable tool has saved my life more than once - and it would save it once again.

Generating Graphviz code is trivial. I had written Graphviz converters before and I didn't doubt for a moment that I could pull off this one. 4tH excels in parsing text and I didn't even need a full parser here. Just

REM,

GOSUB and

GOTO. Since 4tH also features a conversion program template, all I needed to do was to fill in the blanks.

ub2dot.4th was born.

It is basically a very simple 50-lines program. It keeps track of the line it is parsing and when it encounters a

GOSUB or

GOTO it generates a Graphviz line. Of course, if no

GOSUB or

GOTO is encountered, it simply executes the next line. That had to be taken into account as well. But this rule has an exception as well: if the last statement is a

GOTO or

RETURN, the next line will never be reached from that point.

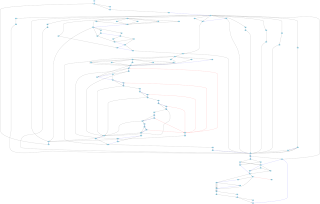

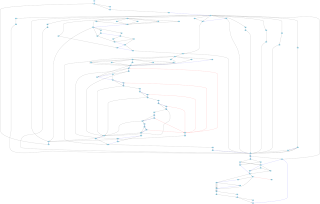

I generated the diagram from the .DOT source, which resulted in this diagram. The black lines are jumps, the red ones are subroutine calls and the blue ones represent normal program flow.

That may not give you much insight at first glance, but when you look carefully, you see some patterns arise. E.g. the code to present the results of the calculation are at the bottom. You can clearly see the different sections for underground explosions and air blasts. At least it helped to chop up the code into manageable chunks.

Since the underground explosions took the least effort, I decided to code that one first. At least it allowed me to set up a basic structure for the program and test it. But first I had a few design decisions to make.

Since this was an all floating point program I decided to use the 4tH Preprocessor (

pp4th).

Floating point support is coded in high level 4tH, which is not supported by 4tH itself. This meant the code would be rather unreadable. The preprocessor however

does offer special floating point facilities, like the entry of floating point numbers without tedious conversions.

4tH offers

two floating point libraries. One is rather bulky and fast with a high precision and its own floating point stack, the other is lean and slow and uses the standard data stack. The latter stores the numbers on the stack in standard form, i.e.

mantissa and

exponent, which is easy to read - if you know what you're looking at. Another added advantage is that it is easier to convert to the dedicated floating point stack version than the other way around.

Forth is a language that is centered around a data stack. It is considered good style to use as few variables as possible. There are non-trivial Forth programs that use only one or two variables or even none at all! However, given the complexity of the task at hand, I decided to use the stack as little as possible and revert to the BASIC variables instead, 25 in all. I never regretted that decision.

Note I had digitized a lot of graphs and these now popped up as clusters of jump instructions, e.g.:

587 IF J2<=-5 THEN GO TO 2007

590 IF J2<=0 THEN GO TO 690

600 IF J2<=5 THEN GO TO 730

605 IF J2<=12.5 THEN GO TO 770

610 IF J2<=25 THEN GO TO 810

630 IF J2<=40 THEN GO TO 840

640 IF J2<=55 THEN GO TO 880

650 IF J2<=62 THEN GO TO 920

660 IF J2<=84 THEN GO TO 960

These were restored to their original table form:

create calc-under

620 , ' under>62 ,

550 , ' under>55 ,

400 , ' under>40 ,

250 , ' under>25 ,

125 , ' under>12.5 ,

50 , ' under>5 ,

0 , ' under>0 ,

-50 , ' under>-5 ,

:this calc-under does>

>r begin fdup r@ @c s>f f% 10e f/ f<=

while r> cell+ cell+ >r

repeat

fdrop r> cell+ @c execute

;

The second entry in the table is a pointer to function, in short: a jump table. The greatest challenge however, was to recreate the spaghetti program flow in structured programming, e.g. from this:

1592 IF J2>=-5 THEN GO TO 1594

1593 GO TO 1596

1594 IF J2<=0 THEN GO TO 1980

1595 GO TO 1600

1596 IF -J5/(J1^.4)>200 THEN GO TO 1600

1597 IF M(1)>M(2) THEN GO TO 1980

1599 IF M(2)<200*(J1^(.4)) THEN GO TO 1980

1600 LET S5=INT ((((((M(2)/1000)*(M(2)/1000))*PI)-(S4/J3))*(J3*.75))+S4)

To this:

J2 f@ f% -5e f<

if

height f@ fnegate yield f@ f% 0.4e f** f/ f% 200e f>

if

S4 f@ density f@ fover fover f/

1 m f@ f% 1000e f/ fdup f* pi f*

fswap f- fswap f% 0.75e f* f* f+ ftrunc S5 f!

else

1 m f@ 0 m f@ fover f> >r

yield f@ f% 0.4e f** f% 200e f* f< r> or

if casualty-corrections then

then

else

J2 f@ f% 0e f>

if

S4 f@ density f@ fover fover f/

1 m f@ f% 1000e f/ fdup f* pi f*

fswap f- fswap f% 0.75e f* f* f+ ftrunc S5 f!

else

casualty-corrections

then

then

I must admit, sometimes I was so desperate that I took refuse to some unconventional techniques in order to get an idea what for Petes sake I was trying to do - thirty years ago.

When I first ran it, it failed obviously. The tedious task of debugging was about to begin. I quickly decided that I would need some special debugging aids in order to complete this task, so I wrote a short routine in both BASIC and Forth that allowed me to examine the variables at certain stages of execution:

9000 PRINT "yield=";J1;" J2=";J2;" density=";J3;" J4=";J4

PRINT "height=";J5

PRINT "P1=";P1;" P2=";P2;" 210J=";R1;" 42J=";R2

PRINT "crater-radius=";S1

PRINT "crater-depth=";S2;" crater-rim=";S3;" S4=";S4;" S5=";S5

PRINT "V1=";V1

PRINT "V2=";V2;" V3=";V3;" V4=";V4;" V8=";V8

PRINT "W1=";W1

PRINT "W2=";W2;" W4=";W4;" Z1=";Z1;" Z2=";Z2

PRINT "Z4=";Z4

FOR N=1 TO 5: PRINT "M(";N;")=";M(N);" "; : NEXT N: PRINT: RETURN

Now you understand why I was so happy that I kept with the original variables instead of going for the full Forth conversion! All in all the basic conversion proved to be pretty good. Only one piece of code needed a full rewrite.

Am I finished yet? No, debugging takes a lot of time - but I'm not in a hurry. At some point in time I will have enough confidence to send it into the world. Hopefully, I will have given it another thirty years of useful life. Time, it wouldn't have had if I had left it in this state.

And that would have been a pity, because it is the oldest program of my hand that survived this long. The rest was left decaying on an ancient 8" floppy. Missing in action, presumably dead. But even if they had survived, would I be likely to repeat this exercise? No, probably not.

Reheating spaghetti takes a lot of time. It's better to cook some fresh pasta. ;-)